Aboriginal observations of new stars appearing in the sky are leading to new approaches in astrophysics research, write Pete Swanton and Duane Hamacher.

Learn how astrophysicists work with Aboriginal elders to describe thousands of years of celestial events in this resource for Year 10 Earth and Space students.

Word Count: approx.1500

Once every few hundred years, our skies are graced by the appearance of a brilliant new star. It can outshine the brightest objects in the sky before gradually fading from visibility over weeks to months. Western scientists call it a supernova, and it represents one of the most cataclysmic events in the universe.

Skywatching cultures the world over have recorded these new stars (novas), from as long ago as ancient China, Arabia and Korea. It is from their written records that astrophysicists first connected the appearance of novas with the nebulous shells of dead stars. New discoveries in modern astrophysics were made by looking back to ancient historical records.

Some astrophysicists looked to the archaeological record for designs and motifs that could be interpreted as supernovas. Without the people who created the motifs to explain what they mean, interpreting and understanding them is extremely difficult. Some scholars made connections between known historical supernovas and rock art, concluding that they were linked. The most famous example is the Chaco Canyon rock art, believed to be of the 1054 CE supernova. Unfortunately, the claims haven’t stacked up against the evidence.

Astrophysicists didn’t look to the oral records of Indigenous peoples. Instead, these records were often dismissed as “myth and legend”. But they’re not myths – they are narratives that encapsulate complex systems of knowledge that are passed down through oral tradition.

The Fisherman Brothers

One example of this comes from Yolgu traditions in eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, where a story passed down is that of the fisherman brothers. One version tells of two young brothers who were fishing out at sea, when suddenly a storm hit them. The brothers began to paddle back to shore as fast as their bark canoe could take them, but the crashing waves quickly overtook them. The eldest brother, Nguruguya-mirri, was a strong swimmer and knew that his younger brother, Napiranbiru, was not. As Napiranbiru began to struggle beneath the waves, Nguruguya-mirri came to his aid and saved his younger brother. But he did so at the expense of his own life.

After the storm passed, someone saw the capsized canoe. People rushed to the shoreline, where they found Napiranbiru, barely conscious but alive. A short time later, his older brother’s lifeless body washed ashore. Napiranbiru told the people how his brother saved his life, and the community held a ceremony that night to honour Nguruguya-mirri’s heroism and sacrifice.

According to the story, a short time later “a bright star shining, new and sparkling” appeared in the sky. The people saw this as a sign that Nguruguya-mirri was now safe with the ancestors. After living a long and full life, Napiranbiru asked the spirit ancestors to place him in the sky with his brother. The pair can now be seen as two bright stars close together in Milnguya (the Milky Way), known in Western astronomy as Shaula and Lesath, the stinger stars of Scorpius.

This story tells of love and support, kindness and sacrifice. It also serves as a warning about fishing too far out at sea at the time of year storms can quickly form out of nowhere. These stars appear in the dawn sky just before sunrise throughout the wet monsoon season, when storms can quickly form.

The appearance of a bright new star appearing in the sky hints at early observations of a supernova. And it gives us important information: it appeared in the Milky Way, is associated with the constellation Scorpius, and it seemed to have faded away (at which point the brothers became the stars Shaula and Lesath). The story describes it appearing on the “banks of the sky river” (Milky Way), indicating it appeared near the boundary between the light and dark spaces in the centre of the galaxy.

Such a description could inform astronomers about where to search for the remnants of dead stars. Do astronomers know of any? Again, the answer is yes, but it wasn’t an Aboriginal story that led to it being discovered, but rather an account from a Chinese scholar in the year 393 CE.

That scholar, Shen Yue, recorded a bright “guest star” in Wěi, an area within the curved tail of Scorpius. The guest star appeared brighter than all the stars in the sky with the exception of Sirius and was visible for eight months before fading from visibility. In 2004 astrophysicists believe they identified the remnant of this stellar explosion, which appeared just four degrees away from Shaula and Lesath, right on the border of the light and dark spaces of the Milky Way.

The Great Eruption of Eta Carinae

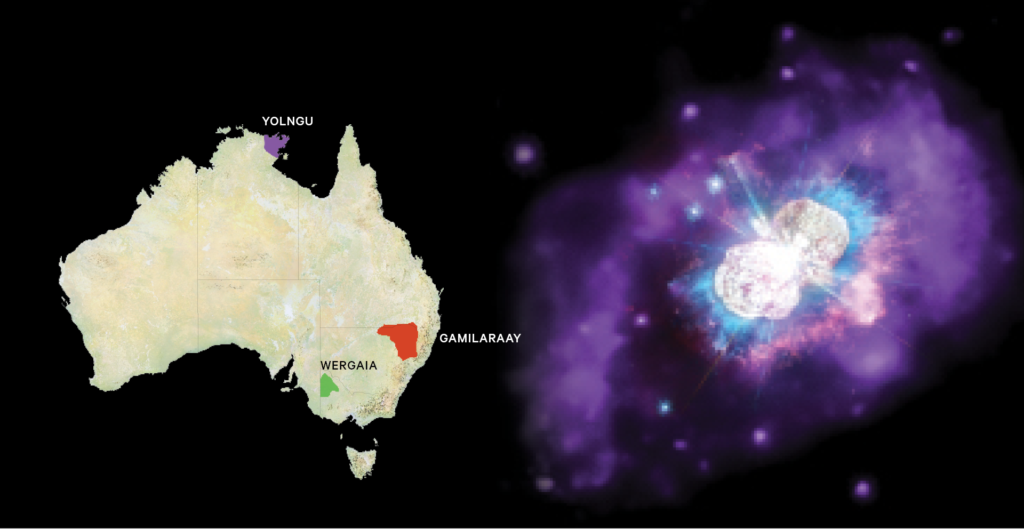

In the early 1840s, an Englishman named William Stanbridge was learning about the star knowledge of the local Boorong people – a clan of the Wergaia, who prided themselves on being the most skilled astronomers around. As they sat by a campfire under the stars next to Lake Tyrrell in northwestern Victoria, two Boorong men pointed out the traditional names and relationships of each star. Stanbridge recorded what the men were telling him, using a star atlas to identify the Western name of each one.

The Boorong astronomers told Stanbridge about War (“wah”) the crow, the second brightest star in the sky (Canopus). They then moved to another bright ruddy-coloured star: Collowgulleric War, the crow-wife. All the faint stars surrounding her were their children. But Stanbridge was confused. His star atlas didn’t show any bright stars in that location. Perplexed, he recorded the star’s appearance, its location in the sky, and its apparent catalogue number. He did not know then – nor did he ever appear to realise – that what the Boorong men pointed out was a rare transient event.

Collowgulleric War represented an enigmatic star undergoing a sudden and extreme period of brightening. This strange star – called Eta Carinae – went from being an inconspicuous star between the Southern Cross and False Cross to become the second brightest star in the sky, fainter only than Sirius (just like the 393 CE supernova). It, too, faded away – but over the ensuing years, rather than the next few months. It also did not blow the star apart, leading astronomers to call it a “supernova-impostor”.

Astronomers referred to it as the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae. Eta Carinae is actually a pair of blue-giant stars, one of which is very unstable, occasionally shedding its outer layers into space. In the early 1840s, Eta Carinae shed the equivalent mass of 20 Suns into space, peaking in brightness in 1843. This debris gradually cooled, encircling the star in a thick layer of dust that caused it to drop in brightness. Twenty years later, it was no longer visible.

The Boorong people had observed this transient event, incorporating it into their traditions as the wife of the nearby bright star Canopus. It stands today as the only Indigenous record of this event anywhere in the world.

Despite this well-known event being visible across the southern hemisphere, no astronomers connected it to the Boorong traditions until 150 years later. Astronomers do know that one day, this star will explode in a magnificent supernova for one final show.

Collaborative Research

Astrophysicists are now working to unlock the processes surrounding the life and explosive death of massive stars, which inform our understanding of the expansion, and the eventual end, of the universe. But this research is now taking a new direction.

We know that Aboriginal traditions contain a great deal of information about the movements of the stars. They also describe a wide variety of transient celestial events, which can stretch back thousands of years. This research now sees Aboriginal elders, astrophysicists and the next generation of Aboriginal astrophysicists working at the intersection of Indigenous knowledge and Western science to find new and innovative ways of understanding our universe in a more inclusive way.

The first approach involves working with Elders to identify oral traditions that describe the appearance of new stars in the sky. This can help astronomers know where to point their telescopes, and the descriptions of these events in the stories can provide important details that can inform and constrain telescopic observations and mathematical calculations.

The second approach involves astronomers scouring the cosmos for the tell-tale signs of exploding stars whose death-throes would have illuminated the galaxy before disappearing forever. Astronomical measurements can tell us how bright they would have been and how long ago they appeared. We collaborate with Elders to identify oral traditions that could have described them.

It is a new and exciting way of learning about the evolution of the universe and our place within it, driven by the people who live and work between two worlds.

Learn more at www.aboriginalastronomy.com.au

This article was written by Peter Swanton, a Gamilaraay/Yuwaalaraay man and astrophysics graduate pursuing a Master’s degree at ANU studying the intersection of Indigenous astronomy, astrophysics, and dark sky studies and Duane Hamacher, Associate Professor of Cultural Astronomy at the University of Melbourne, for Cosmos Magazine Issue 93.

Cosmos magazine is Australia’s only dedicated print science publication. Subscribe here to get your quarterly fill of the best Science of Everything, from the chemistry of fireworks to cutting-edge Australian innovation.

Login or Sign up for FREE to download a copy of the full teacher resource